India Through the Ages

A brief overview of the historical legacy

For the uninitiated, a study of history can be pointless, or boring. It can be a distraction from building a future, or enjoying the present. But often, in order to progress, one must also know ones past. Progress is hardly ever a simple and linear process. Even as society advances in one direction, it loses much along the way. And this has been no less true of India. Delving into the past may seem like a dull and pedantic exercise for some, but to those with an eye on the future, the past can come as a startling revelation.

For that reason, this site is dedicated to the India that is yet to come: hopefully to a more harmonious and just era, when India's citizens enjoy every opportunity towards fulfilling and contented lives. Although the world now has the know-how, the tools and machinery to mechanize and automate production (something that ancient societies lacked), the arrival of modernity hasn't eliminated the need for high culture, for artistic expression and architectural creativity.

Colonization, however, brought drastic changes to India. Even as Europe experienced a cultural upsurge of unparalleled proportions, the reverse occurred in India. Almost extinguished was the spirit of grand experimentation and the sophisticated ornamental fancy that epitomized India's historic architectural tradition. The British, who even in their own country exhibited a rather dour taste in architecture, brought to India a barren functionalism - separated and removed from the needs and the desires of the Indian people. The exuberance of the Indian tradition was mostly supplanted with an architecture that reflected the cold aloofness of the colonial conquerors.

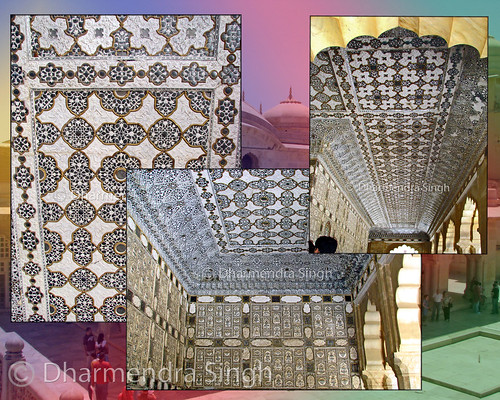

In the past, the very paucity of technology had led our ancestors to a more fecund imagination, to greater flights of fancy, to a more florid vision of the future. Whereas India's ancient architecture is exemplified by its richly sculpted textures, architectural virtuosity and decorative brilliance are the hallmarks of later Indian architecture. Also notable is the sophisticated sense of color that enlivens many of India's palaces, tombs, temples and monasteries. In fact, love of color and decoration permeates the Indian historical ethos. All great Indian architecture employs color or architectural embellishment (or both) with remarkable effect.

Amongst the oldest of India's surviving monuments is the Sanchi Stupa with its sculpted Toranas

and columns dating from around the 1st C BC (or possibly a little later). Less well-known, but nevertheless quite remarkable, is Sarnath's Dhameka stupa (from 500 AD) with its impressive carvings and flowing vegetal motifs.

(Also of note is the Bharuch Stupa, remains of which are on display at the Kolkata museum. Remnants of a Mauryan era Stupa can be seen in Bodh Gaya (Bihar). Especially notable are the Stupas of Andhra Pradesh: such as at Goli, Amravati (most of the remains are on display in the Chennai museum) and Nagarjunakonda (3rd C AD)).

One of the oldest universities of India is Nalanda (Bihar), one of the largest of the ancient world, once drawing scholars from all across Asia. It still retains the unmistakable air of a college campus, and one of its temples has some engaging carvings.

Approaching the ruins Monastery View from the upper floor Shrine across Monastery

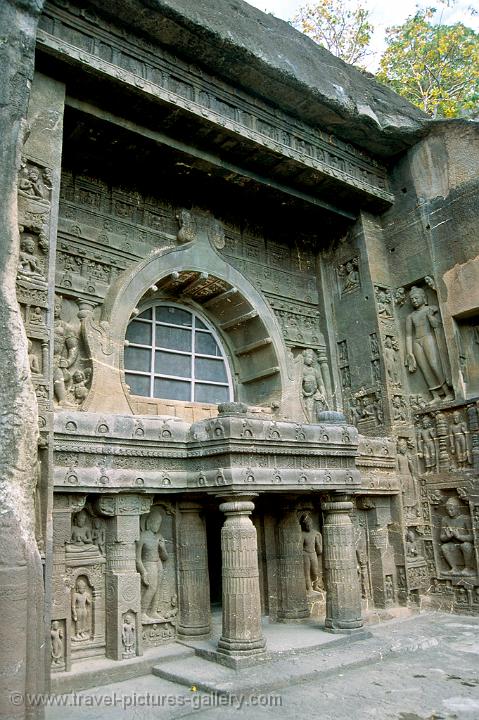

In the Northern Deccan are the Chalukyan temple towns of Aihole, Pattadkal, Badami and Alampur, with many attractive examples of 7th-9th century sculpture that rival those of Ajanta, Ellora and Elephanta.

Buddha image inside an Ajanta cave janta - Ellora - the Buddhist caves of Ajanta

- Ajanta - Ellora - elephants carved at an Ajanta cave entrance

Throughout Central India (particularly in the Chhatisgarh region), there are several monumental temples. Some are small and graceful like the Char-khamba and Ath-khamba temples in Gyaraspur. Others are bold and imposing, such as the unfinished temple at Bhojpur near Bhopal. Scattered throughout the region, in places like Deogarh and Mandsaur, (and in small museums like Vidisha's) are exceptional examples of Central Indian sculpture Near the border with Gujarat, the seldom visited 7th century Bagh caves (with their unexpectedly grand columns) are quite a wondrous surprise. (See India Revealed: Gallery of Indian Sculpture)

Tamil Nadu is renowned for its impressive Pallava (Mahabalipuram) and Chola heritage. Narthamalai's hill-top 7th century temple, Sittanvasal's painted Jain cave, the temples in Srirangam, Chidambaram, Darasuram, Tanjore and Gangaikondacholapuram are amongst the most interesting.

Image of Sri Ramanuja "as he was"

Amongst Gujarat's cultural treasures is the 11th century Rani-ni-Vav (Queen's Step Well) in Patan

(old capital of North Gujarat) boasting one of the countries finest sculpture galleries. Sculptures in the 11th century Sun-temple atModhera evoke different moods: some an absorbing seriousness, others a sensuous and earthy vitality. Also impressive are the ornate temples of Orissa.

With the exception of some exquisite gateways (such as those in Gyaraspur, Vadnagar, Warangal and Nagda, near Udaipur, Rajasthan) Indian architecture up to this point is distinguished more by its exuberant sculpture and ornate carving than by grandly handsome structural features. After the 12th century, one begins to see the proliferation of Islamic monuments in Northern India - many of which were built over older Hindu, Jain or Buddhist temples or monasteries. This led to a dramatic change in form and style.

As representations of the human form became taboo with the advent of Islam, abstraction triumphed over traditional Indian naturalism and symbolism. However, abstract decorative motifs from earlier Indian monuments were retained in the later Islamic monuments, often with great effect. Cultural continuities are particularly apparent in the mosques of Gujarat and Bengal.

In Bengal, the architects and artisans borrowed heavily from the earlier repertoire, seamlessly recycling architectural elements from the temples and monasteries that were replaced. The results were often quite spectacular. Pandua's 14th century Jama Masjid (picture above) is one of the

most imposing in the sub-continent. Gaur, the former capital of Mughal Bengal is home to several mosques with delicately chiseled brickwork and impressive poly-chrome tile-work.

most imposing in the sub-continent. Gaur, the former capital of Mughal Bengal is home to several mosques with delicately chiseled brickwork and impressive poly-chrome tile-work.

The Gujarat Sultanate was founded by a Jain convert to Islam, and motifs considered auspicious in the Hindu and Jain tradition found their way into mosques and palaces in Ahmedabad, Champaner, Sarkhej, Surat and other cities. Variants of the Jain lamp of learning are to be found in several of Ahmedabad's mosques, and the exquisite Kalp-Vriksh motifs that enliven the mosques and tombs of Ahmedabad and Champaner harken back to the Ranakpur and Dilwara temples as do the grand and ornate ceilings, and handsomely carved columns that are the hallmark of Gujarat's impressive mosques. Decorative Jaalis which are used with ingenious effect in the Rauzas at Sarkhej and Ahmedabad undoubtedly derive from the finely-wrought Jaalis in Palitana (Bhavnagar). It may be worth mentioning that some of Ahmedabad's finest mosques (such as the Rani Sipri and Rani Rupmati) were commissioned by the Hindu wives of the rulers of the Gujarat Sultanate.

Jaunpur (UP), seat of the Sharqi Rajahs, also has some intriguing mosques that reach imposing heights and are embellished with very finely crafted jaalis. Fine jaalis are also to be found in the Madrasa in Dhar. In Chunar, in Eastern UP, there are some spectacular monuments from the time of Sher Shah Suri. Although the Mughal era is best exemplified by the monuments in Agra, Delhi and Lahore, fine examples of Mughal tombs can also be seen in Burhanpur,Meirut and Allahabad. In Nakoddar (Punjab), there are two gorgeous Mughal era tombs with brilliant polychrome decorations.

Jaunpur (UP), seat of the Sharqi Rajahs, also has some intriguing mosques that reach imposing heights and are embellished with very finely crafted jaalis. Fine jaalis are also to be found in the Madrasa in Dhar. In Chunar, in Eastern UP, there are some spectacular monuments from the time of Sher Shah Suri. Although the Mughal era is best exemplified by the monuments in Agra, Delhi and Lahore, fine examples of Mughal tombs can also be seen in Burhanpur,Meirut and Allahabad. In Nakoddar (Punjab), there are two gorgeous Mughal era tombs with brilliant polychrome decorations.

In Gulbarga, Bidar and Bijapur - there are remnants of the sophisticated courts of the Deccani Nawabs. Profusely ornamented (often with colored tiles) - their Islamic monuments are easily differentiated from those of the north with their characteristic domes and turrets.

Hyderabad, capital of the fabulously wealthy Golconda Nawabs was once a thriving medieval metropolis, particularly famous for its pearl-trade. Its affluence attracted superb craftspeople and its rulers commissioned some of the most magnificent monuments in all of India. Tombs and mosques - grand and whimsical, are scattered in and around the city. The Qutab Shahi and Paigah tombs are veritable museums of architectural decoration. And while little of the original polychrome tile work has survived - what has is quite spectacular.

In the north, Lucknow, Faizabad, Bhopal and Murshidabad emerged as culturally important courtly centers following the decline of the Mughals.

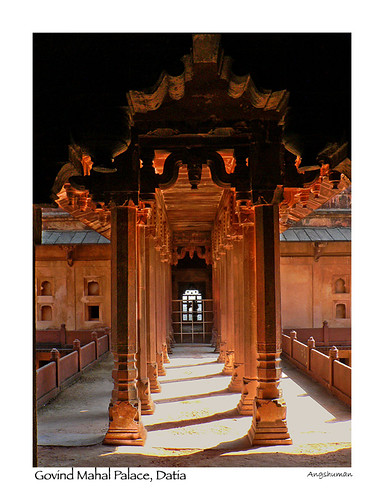

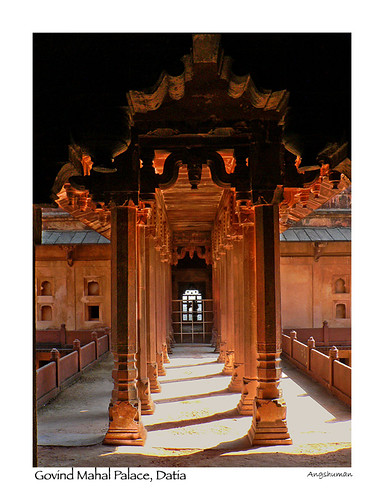

Rajput courts developed in parallel with the Mughal and Deccan courts, and the courts of Bikaner, Jodhpur and Jaipur rivaled those of their Mughal counterparts. one of the most endearing aspects of the decor in their palaces is the very effective use of color, and the unabashed integration of folk elements in royal designs. Whimsical and quixotic, the forts and palaces of Rajputana, Bundelkhand, and the hill regions of Garhwal and Himachal boast especially fine Chitra-Shalas (art-galleries).

Bundi, Jhalawar, Kota, Nahaargarh, Jaigarh, Nagaur and Karauli in Rajasthan, Datia, Jhansi and Orchha in Bundelkhand, and Damtal, Nurpur, Chamba and Kulu in Himachal - all have frescoes and wall paintings that attest to the love of art. In the royal chambers in Datia's palace, flowing

arabesques and stylized nature scenes form a seamless and organic fusion of abstract and naturalist decorative elements that charm and dazzle the eye. Birds and flowers make particularly popular decorative motifs, and the royal Chhatris in Datia and Shivpuri make ample and effective use of them. In the south, Ramanathapuram's Maratha palace with it's whimsical wall-paintings is especially noteworthy (as are the wall-paintings in Madurai, Thanjavur and Lepakshi). (Also see Legacy India)

arabesques and stylized nature scenes form a seamless and organic fusion of abstract and naturalist decorative elements that charm and dazzle the eye. Birds and flowers make particularly popular decorative motifs, and the royal Chhatris in Datia and Shivpuri make ample and effective use of them. In the south, Ramanathapuram's Maratha palace with it's whimsical wall-paintings is especially noteworthy (as are the wall-paintings in Madurai, Thanjavur and Lepakshi). (Also see Legacy India)

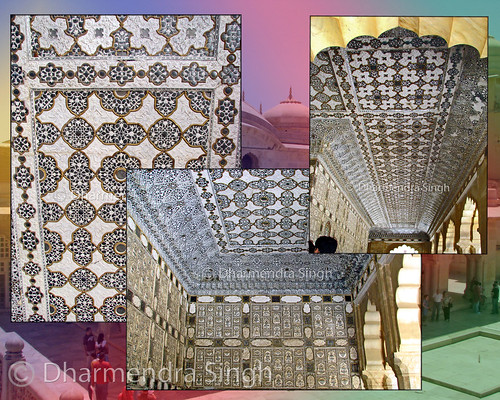

In West Bengal, Tripura, Assam and Manipur, temple architecture owed much to vernacular designs, (as in Jammu and Kashmir). Assam's Vaishnava shrines are particularly noteworthy for their enchanting folk paintings. Folk influences were also significant in some of the monasteries and Gurudwaras of Punjab such as at Pindori Darbar (near Gurdaspur). As the Sikhs rose to replace Mughal rule in Punjab, they developed their own unique style drawing upon both Mughal and Rajput tradition. Agra and Bikaner appear to be the inspiration for much of the decor in the Golden Temple in Amritsar, and the Sheesh Mahal

in Patiala.

Sheesh Mahal.

Sheesh Mahal.

Patiala's Qila Mubaraq is unusual though characteristic.

in Patiala.

Sheesh Mahal.

Sheesh Mahal.Patiala's Qila Mubaraq is unusual though characteristic.

The decline of the Mughals also led to the rise of the Jatts in areas near Delhi, and the palaces in Ballabgarh and Deegh are especially notable. Also of interest are the many Havelis of Northern India (such as in Etawah) or in several small towns in Haryana (which was once dotted with several prosperous Mughal administrative towns such as Palwal, Faridabad and Narnaul - where there are unusual Mughal tombs in red sandstone and dark granite). Dujana and Farukhnagar (both near Gurgaon), have several fine Havelis.